Transforming an organization is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle – a series of interconnected pieces must be placed together with care in order for the final picture to materialize. But unlike a puzzle, in an organization these pieces aren’t cardboard cutouts – they’re real people with their own priorities, politics, and processes in place. This means implementing change, whether it be a new business strategy, market approach, operating model, or reorganization, often requires more thought, planning and finesse than initially expected. To continue the puzzle analogy, reshaping the pieces, redesigning the artwork, and adding, removing, or replacing individual pieces, will affect the whole finished product (whether or not you intend it to). This article introduces 6 key considerations for implementing effective change that will help you fit all of the pieces together.

Elements of Organizational Change

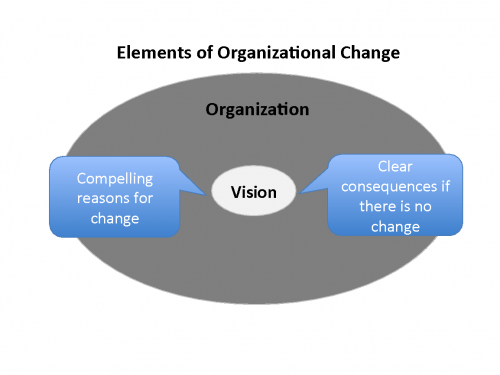

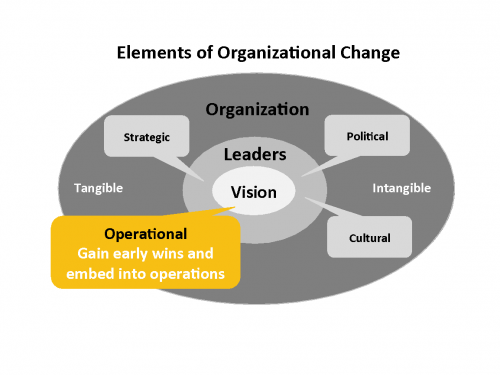

This change model allows you as a change leader to consider a 360-degree view of the organizational dynamics as play, including your own journey of change. The first step is to carefully consider how the following six dimensions currently align with the transformation you are making:

- Vision Alignment – Does this change connect to your organization’s compelling vision?

- Leader Alignment – How will your leaders kick start the journey of change?

- Strategic Alignment – How will this change be anchored in a long-range strategy?

- Political Alignment – How will influential leaders align with the change objectives?

- Cultural Alignment – How will the culture of the organization shape this change?

- Operational Alignment – How will the change eventually become ‘business as usual’?

Consideration #1 – Vision Alignment

To successfully implement transformation in an organization leaders must first have a compelling answer to the question, “Why change?”

Many leaders are unsuccessful because they move too quickly on operationalizing change and underestimate the amount of complexity and human engagement that is required in the process. As Peter Senge says, “people don’t resist change, they resist being changed.”

In any organization, people need to understand why change needs to happen and how it may impact to enable them to buy into the change process. Even if the news is negative such as the downsizing of an operation, people will be more likely to accept the news if there are satisfying justifications behind it. The range of answers you may provide to the question, “Why change?” can vary from business to moral reasons. But these answers should bolster a compelling vision of the benefits for change in ways that people can understand and relate to. Also, people need to be convinced that the consequences of not changing are significant enough to create a sense of urgency to act, sometimes referred to as a ‘burning platform’.

How you communicate this vision matters. The more significant the change is to the organization, the more important in-person messaging becomes to not only convey the importance of the change at hand, but also to convey the value and importance of those impacted by the change. Key people involved and impacted by the change need to see and hear their leaders so they can truly ‘sense’ the change and internalize the messages being delivered, especially if the news is difficult. Our experience has been that leaders often underestimate the amount of communication and engagement it requires to create a shared sense of understanding and buy-in with employees. It is easy to assume that people will catch on and buy-in more quickly than they do.

- How will you lead change with a vision that appeals to the hearts and minds of people?

If you do so consistently, authentically and truthfully, you will be more likely to create partners, participants and advocates and minimize the resistance that may exist.

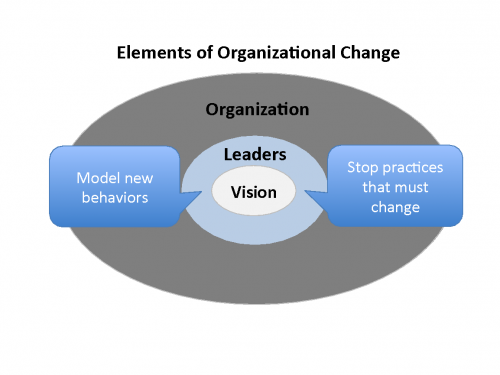

Consideration #2 – Leader Alignment

Implementing change starts with the internal journey of a leader. Whether charting a new vision, making a significant strategic pivot in your organization or implementing a new system, change can be both energizing and fear-inducing at the same time. Facing change can raise questions and insecurities inside the hearts and minds of leaders. What happens if this doesn’t work? Do I have what it takes to do this? How will I navigate the challenges? How will I find new solutions to new unseen challenges? Will people still like me and respect me? A leader must choose the courage to risk rather than succumb to fear.

The most difficult changes for leaders often involve modifying their own mindsets and work habits. Leo Tolstoy once said, “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.” New behaviors must start and old behaviors must stop. This is true for how an organization operates, how a leader manages the organization, and how leaders manage themselves. To stop doing something old is often the more difficult part because the ‘old’ things may be the very areas in which we are most comfortable, confident and competent.

Good leaders dig deeper and reflect on how their values, practices and core beliefs may need to internally align as they embark on a change process. They model the way forward, not just describe it. Some examples of internal change we’ve seen in leaders include clear choices, such as: demonstrating transparency, showing empathy, dealing with a festering conflict, personally committing to living out the stated values of the organization. One powerful example is a very senior leader permanently giving up personal office space so that other team members had more regular access for meeting space. The signal was clear: the work being done is more important than the status I have as your leader.

As a leader, it will be important for you to be transparent with your people about your own journey of change to help them identify with you as they go through the process of starting something new and stopping something old. If you take time to reflect on this and then apply these leadership practices and behaviours, you will begin to model the very change you are introducing to the organization.

- What do you need to do that is new and what do you need to stop that is old?

Consideration #3 – Strategic Alignment

The change you are introducing can take root more quickly if it is fully aligned with the strategic direction of the organization. While this may seem obvious, it is surprising how organizations can misstep here, especially in large organizations where strategic planning and execution are more decentralized. Managers at different levels can interpret the intentions of strategic objectives quite differently and sometimes ignore these objectives altogether.

A large international organization implemented a new global marketing strategy without considering the best way to align with its regions that were executing against their own marketing strategies. The global leaders jumped ahead to ‘sell’ their own marketing plans without truly considering the operating cycles and plans of regional leaders. The strategic intention was for global corporate head office to support the efforts of the regions, but in fact, they were duplicating efforts and creating tension between global and regional offices. After recognizing that the new initiative was failing, they repositioned in a more consultative manner ensuring that they were aligned on the same strategic objectives.

Before implementing change, consider:

- Do I share the same understanding of the strategic objectives with other key leaders?

- How can I use the strategic direction of the organization to answer the question “Why change?”

Consideration #4 – Political Alignment

It is dangerous to believe that major transformations are the result of just one highly visible individual in the organization, says John Kotter. A team of allies is required at many levels in the organization to ensure success. Early in the change process it is vital to ensure key that key influencers and decision-makers support the initiatives. Influencers such as board members, key executive team members and line managers who may not even be directly involved in the process but hold the keys to providing resources and eliminating roadblocks, are vital for success. It is important not to make assumptions about the actual support you may have for the change ahead. One new CEO in a technology service company decided to move ahead with a change process in the midst of a significant system implementation already underway. Leaders were not happy but no one directly challenged this decision. The CEO could not read the signals and the lack of real political support among his team led to passive aggressive behaviors from the senior team. With the process failing, new timelines and expectations were created that were more realistic that the entire team could support.

Political alignment is intangible and can therefore be difficult to anticipate. Consider asking for direct support in a change process from leaders that you will depend upon for success and spell out what support you are looking for. Other benefits you may gain from direct conversations is that you will identify potential challenges or concerns that they may have but not be willing to share in executive team settings.

Before implementing change, consider the following:

- Do the key power brokers that could make or break the success truly support this initiative?

- Do I have enough insight, expertise on and various points of view on my team that can inform our decision-making?

Consideration #5 – Cultural Alignment

“Culture eats strategy for lunch,” says Peter Drucker. Organizational culture is a power force that is often underestimated when implementing change. It includes the collection of values, practices and beliefs that describe ‘how we do things around here.’

- Stated Values: The stated values and approaches of the organization describe the personality and soul of organization. Values are both descriptive and aspirational in nature, pointing to what the organization is like and what the organization wishes to be like. Values most often revolve around the categories of teamwork, the workplace environment, attitudes, client success, value creation and innovation.

- Practices: These are the protocols, processes and behaviors that embody how to work together as an organization. Practices can be quite diverse and include elements as diverse as how decisions get made, how the organization collaborates (or doesn’t), the acceptable dress code and how physical workspace is configured.

- Underlying Beliefs: These are underlying assumptions about what is normative and acceptable and are rooted in the history of the organization. Because they are unstated, they are often difficult to articulate and address directly. Some example include beliefs about how leaders should use power, the appropriate level of openness to new ideas, the relative importance of tradition, how to handle conflict, the relative importance of transparency and openness.

The senior leader of a governmental organization astutely recognized the complexity of many cultural dynamics in her organization including five different union cultures represented. In the design stage of the process she gathered key decision-makers and influencers at all levels of the organization to discuss the culture shifts needed. This ultimately became a blueprint for a change strategy that lasted over five years.

Culture drivers are like strong currents that can take change processes off course. Consider the fact that 30% or more of mergers and acquisitions fail because organizational cultures are not compatible. Leaders must reckon with the intangibility of culture dynamics ‘under the iceberg’ in order to successfully implement change. It can be helpful to use a culture inventory to identify possible conflicts in advance so they may be pre-empted. To start, ask those involved in the change what the most important values are to them. Resistance behaviors are often symptoms of culture conflict in change processes when the following occurs:

- Loss of control – protecting territory and decision-making authorities

- Uncertainty – holding back because of ambiguity about what lies ahead

- New work patterns – resisting new ways of working that require more upfront effort

- Changing from the past – viewing the ‘new’ as disrespecting the ‘old’

- Dividing lines – rekindling resentments from past conflicts

When culture collisions occur, they create opportunities to have conversations with those involved about what is important to them and why. In many cases, the underlying beliefs need to be named and articulated openly in order for cultural renewal to happen.

Consider the following as you implement change:

- How do stated values, practices and underlying beliefs of your organization align with the changes you are making?

- How will you introduce cultural change to support your change initiative?

Consideration #6 – Operational Alignment

Change processes are about moving from the operation you have to the operation you need to become. Attend too much to the former and change is too incremental, losing momentum. Change too quickly and the current operation cannot deliver today to sustain the organization.

The following principles can serve to guide you at your pace and sequence change implementation:

- Seek early success: Deliver some short-term wins to demonstrate what the future will look like and that it can be successful. This will establish greater credibility and help win over some laggards and skeptics who simply need to see what concrete impact the change will make.

- Operationalize the ‘new’: When an early success is achieved, embed the change in into the operational workflow to make it the new ‘business as usual’. In this way the next phases of change become the focus and the past changes will soon become the new routine.

- Expand learning: Use the early successes and failures to stimulate new learning and update the change plan. Time for learning is vital to stimulate success and should not be confused with reporting and planning activity. It is the place to discover insights about the impact of the changes that are not necessarily obvious.

- Keep structures flexible: Organizational structures should be adaptable to allow for expansion and growth. Good change mangers de-emphasize hard structures and territories but emphasize but flexibility and adaptability that enable ‘matrixed‘ leaders to facilitate the success of projects.

- Emphasize shared objectives: The best way to integrate change within the organization is to establish shared objectives among operating units. The more that teams are responsible for shared objectives, the more that they will work together so that they can share success.

- Reward risk-taking: In more traditional risk-averse organizations, change requires taking responsible risk-taking. If failures result, it is important to learn and move ahead without creating negative repercussions for the risk-takers. Instead, reward and recognize individual risk-takers and teams who are willing to break the familiar molds.

Consider the following as you implement change:

- What change implementation principles need careful planning?

- How will you embed new changes to become ‘business as usual’?

Summary

As you lead your organization and take stock of these various areas of alignment, you can gain insight on where you may need to spend time developing your change plan. Remember, change first starts with you as a leader and the vision you articulate for your people must be compelling. Ultimately, it is the people, not inanimate systems, who must change. Therefore, what you model by way of behavior serves to reinforce the vision and give you credibility. Change happens within an organizational ecosystem so any foreseeable impacts should be considered at the same time. Be sure to have a shared understanding of the strategy with other key leaders and be aware of where you stand with their support. Assess the possible cultural conflict advance and open up discussions about underlying beliefs that you suspect may be at work. Finally, be sure to have a roadmap gaining early wins to consolidate credibility and support.